[an error occurred while processing this directive] [an error occurred while processing this directive]

![]()

![]()

This discussion is drawn from Section 4.2, pages 59-63; Section 4.3, pages 66-69; Section 5.3, pages 75-76; and Section 5.4, pages 77 - 81 of The Mathematics of Financial Derivatives: A Student Introduction by P. Wilmott, S. Howison, J. Dewynne, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995. Some ideas are also taken from Chapter 11 of Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications by J. Michael Steele, Springer, New York, 2001.

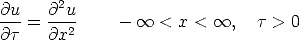

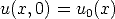

We have to start somewhere, and to avoid the problem of deriving everything back to calculus, we will assert that the initial value problem for the heat equation on the infinite interval is well-posed, that is, the solution to the partial differential equation

with

where the initial condition and the solution satisfy the following technical requirements:

u0(x)e-ax2 = 0 for any a > 0,

u0(x)e-ax2 = 0 for any a > 0,

u(x,

u(x, )e-ax2 = 0 for any a > 0

)e-ax2 = 0 for any a > 0

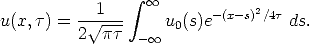

exists for all time, is unique, and most importantly, can be represented as

Remark: This solution can derived in several different ways, I think the easiest way is to use Fourier transforms. The derivation of this solution representation is standard in any course or book on partial differential equations.

Remark: Mathematically, the conditions above are unnecessarily restrictive, and can be considerably weakened, however, they will be more than sufficient for all practical situations we encounter in mathematical finance.

Remark: The use of  for the time variable (instead of the more

natural t) is to avoid a

conflict of notation in the several changes of variables we

will soon have to make.

for the time variable (instead of the more

natural t) is to avoid a

conflict of notation in the several changes of variables we

will soon have to make.

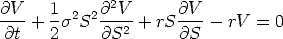

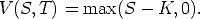

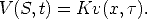

The Black-Scholes terminal value problem for the value V (S,t) of a European call option on a security with price S at time t is

with V (0,t) = 0, V

(S,t) ~ S as

S

and

and

Note that this looks a little like the heat equation on the infinite interval in that it has a first derivative of the unknown with respect to time and the second derivative of the unknown with respect to the other (space) variable, but notice:

, but although this is financially

sensible, (it says that for very large security prices, the

call value with strike price K

is approximately S) it is more

in the nature of a technical condition, and we will ignore

it without consequence.

, but although this is financially

sensible, (it says that for very large security prices, the

call value with strike price K

is approximately S) it is more

in the nature of a technical condition, and we will ignore

it without consequence.

We will eliminate each and every one of these objections with a suitable change of variables. The plan is to change variables to reduce the Black-Scholes terminal value problem to the heat equation, and then to use the known solution of the heat equation to represent the solution, and change variables back. This is a standard technique of solution in partial differential equations, and none of the transformations we are making are strange, unmotivated, or unknown.

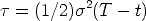

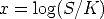

First we will take t = T - and S = Kex,

and we will set

and S = Kex,

and we will set

Remember,  is the volatility, r is the interest rate on a risk-free bond,

and K is the strike price. In

the changes of variables above, the choice for t reverses the sense of time, changing the

problem from backward parabolic to forward parabolic. The

choice for S is a well-known

transformation based on experience with the Euler

equidimensional equation in differential equations. In

addition, the variables have been carefully scaled so as to

make the transformed equation expressed in dimensionless

quantities. All of these techniques are standard and are

covered in most courses and books on partial differential

equations and applied mathematics.

is the volatility, r is the interest rate on a risk-free bond,

and K is the strike price. In

the changes of variables above, the choice for t reverses the sense of time, changing the

problem from backward parabolic to forward parabolic. The

choice for S is a well-known

transformation based on experience with the Euler

equidimensional equation in differential equations. In

addition, the variables have been carefully scaled so as to

make the transformed equation expressed in dimensionless

quantities. All of these techniques are standard and are

covered in most courses and books on partial differential

equations and applied mathematics.

Some extremely wise advice adapted from page 186 of Stochastic Calculus and Financial Applications by J. Michael Steele. Springer, New York, 2001 is appropriate here.

|

“There is nothing particularly difficult

about changing variables and transforming one

equation to another, but there is an element of

tedium and complexity that slows us down. There is

no universal remedy for this molasses effect, but

the calculations do seem to go more quickly if one

follows a well-defined plan. If we know that V (S,t) satisfies an equation (like

the Black-Scholes equation) we are guaranteed that

we can make good use of the equation in the

derivation of the equation for a new function v(x, |

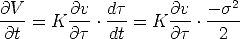

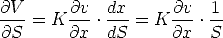

Following our advice, we first have to write

and

so

and

and

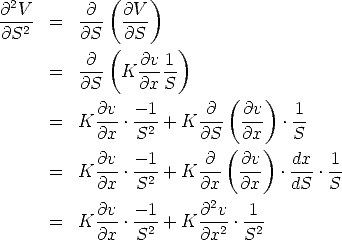

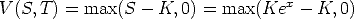

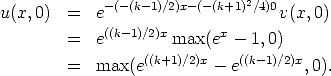

and the terminal condition

but V (S,T) = Kv(x, 0) so v(x, 0) = max(ex - 1, 0).

Now substitute all of the derivatives into the Black-Scholes equation to obtain:

Now the simplification begins:

-derivative to the other side, and divide

through by

-derivative to the other side, and divide

through by  2/2

2/2

2/2) as k.

k measures the ratio between

the risk-free interest rate and the volatility.

2/2) as k.

k measures the ratio between

the risk-free interest rate and the volatility.

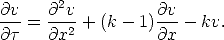

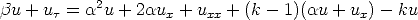

What remains is the rescaled, constant coefficient equation:

We have made considerable progress, because

2T , not

the original 4 dimensioned quantities, namely K, T,

2T , not

the original 4 dimensioned quantities, namely K, T,  2

and r.

2

and r.

< x <

< x <  , since this x-interval defines 0 < S <

, since this x-interval defines 0 < S <  through the change of

variables S = Kex.

through the change of

variables S = Kex.

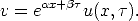

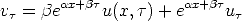

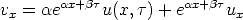

Instead, we will change the dependent variable scale yet again, by

where  and

and  are yet to be determined. Now using the

product rule:

are yet to be determined. Now using the

product rule:

and

and

Put these into our constant coefficient partial differential

equation, cancel the common factor of e x+

x+

throughout and obtain:

throughout and obtain:

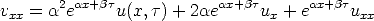

Now gather like terms:

![2 ut = uxx + [2a + (k - 1)]ux + [a + (k - 1)a - k - b]u.](solution20x.png)

Then choose  = -(k

- 1)/2 so that the ux

coefficient is 0, and then choose

= -(k

- 1)/2 so that the ux

coefficient is 0, and then choose  =

=  2 + (k -

1)

2 + (k -

1) -

k = -(k +

1)2/4 so the u

coefficient is likewise 0. With this choice, the equation is

reduced to

-

k = -(k +

1)2/4 so the u

coefficient is likewise 0. With this choice, the equation is

reduced to

We also need to transform the initial condition too. This would be

For future reference, we notice that this function is strictly positive when the argument x is strictly positive, that is u0(x) > 0 when x > 0, otherwise, u0(x) = 0 for x < 0.

Now we are in the final stage, since we are ready to apply the solution representation formula:

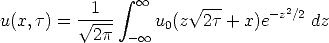

However, first we want to make a change of variable in the

integration, by taking z =

(s - x)/ , (and

thereby dz = (-1/

, (and

thereby dz = (-1/ ) dx) so that the integration becomes:

) dx) so that the integration becomes:

We may as well only integrate over the domain where u0 > 0,

that is for z > -x/ . On that

domain, u0 = e((k+1)/2)(x+z

. On that

domain, u0 = e((k+1)/2)(x+z )

- e((k-1)/2)(x+z

)

- e((k-1)/2)(x+z ) so we are down to:

) so we are down to:

Call the two integrals I1 and I2 respectively.

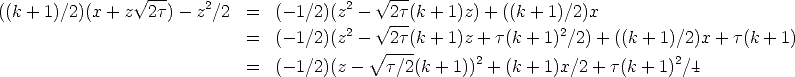

We will evaluate I1 ( the one with the k + 1 term) first. This is easy, just completing the square in the exponent yields a standard, tabulated integral. The exponent is

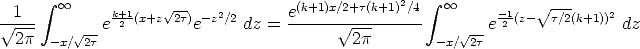

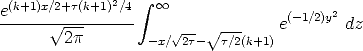

Therefore

Now, change variables again on the integral, choosing y = z

- (k + 1) so dy = dz, and

all we need to change are the limits of integration:

(k + 1) so dy = dz, and

all we need to change are the limits of integration:

The integral can be represented in terms of the cumulative

distribution function of a normal random variable, typically

denoted  . That

is,

. That

is,

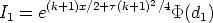

so

where d1 = x/ +

+  (k + 1) (note the use of the symmetry

of the integral!) The calculation of I2 is

identical, except that (k + 1)

is replaced by (k - 1) throughout.

(k + 1) (note the use of the symmetry

of the integral!) The calculation of I2 is

identical, except that (k + 1)

is replaced by (k - 1) throughout.

That, is the solution of the heat equation is

where d1 = x/ +

+  (k + 1) and d2 =

x/

(k + 1) and d2 =

x/ +

+  (k - 1).

(k - 1).

Now, we must systematically unwind each of the changes of

variables, from u, first v(x, ) = e(-1/2)(k-1)x-(1/4)(k+1)2

) = e(-1/2)(k-1)x-(1/4)(k+1)2 u(x,

u(x, ). (Notice

how many of the exponentials neatly combine and cancel!) Then

put x = log(S/K),

). (Notice

how many of the exponentials neatly combine and cancel!) Then

put x = log(S/K),  = (1/2)

= (1/2) 2(T

- t) and V (S,t) = Kv(x,

2(T

- t) and V (S,t) = Kv(x, ).

).

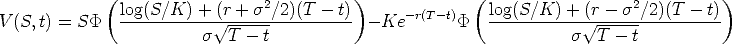

The final solution is the Black-Scholes formula for the value

of a European call option at time T with strike price K, if the current time is t and the underlying security price is S, the risk-free interest rate is

r and the volatility is  :

:

Note, usually one doesn’t see the solution as this full closed form solution. Instead, most versions of the solution write intermediate steps in small pieces, and then present the solution as an algorithm putting the pieces together to obtain the final answer.

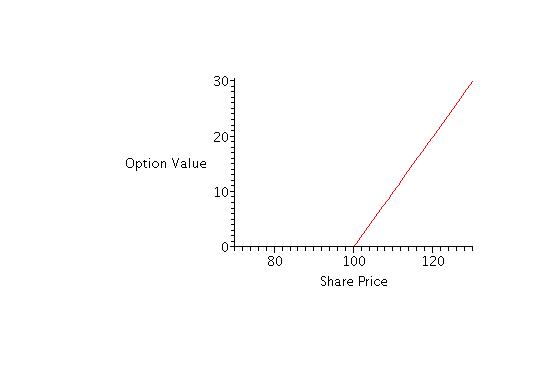

Consider for purposes of graphical illustration the value of

a call option with strike price K = 100. The risk-free interest rate per

year, continuously compounded is 12%, so r = 0.12, the

time to expiration is T = 1

measured in years, and the standard deviation per year on the

return of the stock, or the volatility is  . The value of

the call option at maturity plotted over a range of stock

prices 70 < S

< 130 surrounding the strike price

is illustrated below:

. The value of

the call option at maturity plotted over a range of stock

prices 70 < S

< 130 surrounding the strike price

is illustrated below:

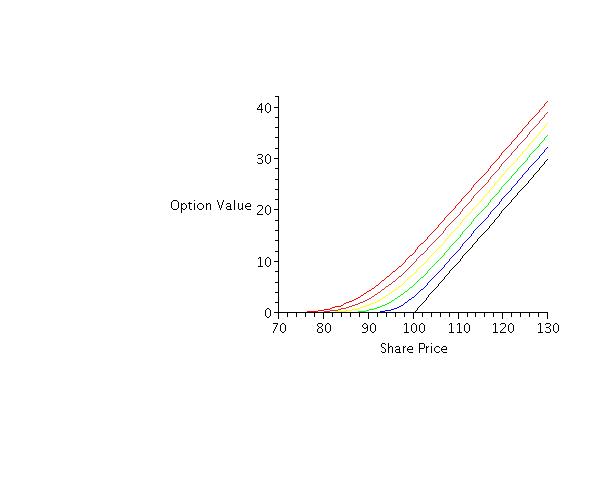

Now, we use the Black-Scholes formula above to compute the value of the option prior to expiration. With the same parameters as above the value of the call option is plotted over a range of stock prices 70 < S < 130 at time remaining to expiration t = 1 (red), t = 0.8, (orange), t = 0.6 (yellow), t = 0.4 (green), t = 0.2 (blue) and at expiration t = 0 (black).

Notice a couple of trends in the value from this graph:

We can also plot the solution of the Black-Scholes equation as a function of security price and the time to expiration as value surface:

and other elementary

functions as was done for the integral I1.

and other elementary

functions as was done for the integral I1.

T.

T.

[an error occurred while processing this directive] [an error occurred while processing this directive]

Last modified: [an error occurred while processing this directive]